Thursday 11th September

I had meant to stick to Wednesdays as my British Library day but bombing it to Snowdonia and back on a speculative mission stopped that this week. Today I get acclimatised, work out how things work, how to order up books, newspapers, rare print. I will start with the books on my reading list: ‘The Federal Theatre Project 1935-1939: engagement and experimentation’, ‘Bread and Circuses: A Study of Federal Theatre’….

I’d forgotten that on the list of things not allowed in the reading rooms are pens. Pencils are the tool here. Joined and probably superseded by digital device but still… I hold it carefully, aware of how it could quite easily become defunct without an accompanying pencil sharpener. No sharp objects allowed. Perhaps there is also something in this restriction. If only pencils are allowed maybe I work with that. Might not be that linked to my main aims but another way of documenting and recording time here in a different way?

Being unprepared for compulsory graphite, I was forced to buy a pencil for 50p from the shop. As I’d already packed away all cash I browsed to add something to the order and projects collided as I reached, as always, for a sunflower – a card of an image taken from Hortus Eystettensis, originally published by George Mack, Nuremburg 1931. A sunflower recorded as war brewed. It sits next to the Birthday cards stating ‘another year around the sun’ - all these dizzying years of humanity spinning around the sun - of trauma and tragedy, joy and justice. Gutenberg Press. Nuremberg Chronicles. Nuremberg Trials. Reading the information boards and looking at the select displays in the vast public spaces of the library makes clear this history of the printed word and its political implications. The acknowledgement that the library holds items that were originally acquired through the profits from slavery or imperial theft. One of the collections that merged to become the British Library was ‘The India Office Library and Records’ assembled by the East India Company and India. The consequences of words stolen, erased or repurposed.

As I take a clear plastic bag labelled Reading Room Requirement I see a stack of flyers – ‘London is Anti-Fascist.’ This is a clear and needed statement but it is not a given. Democracy takes constant work – a process undermined by words becoming laws until the only word is oppression. When George Orwell says ‘our times’ from his desk somewhere in the 1940s he speaks to ours. An extremely slim pamphlet in the distinctive new white and red Penguin series see his words speaking out from bookshop displays across the country – ‘Fascism and Democracy.’ I pick it up and walk through the biographies of Musk, the voices of minor celebrities, sporting legends, the bestseller lists, stacked crime fiction and recipes towards the till where it faces me again - forcing us to confront some truth amid the fluff and loveliness. (See Hugh Bonneville on the red carpet of Downton Abbey’s premiere). And if I ‘m always struck by how many new books are on display in the bookshops and those I wish were not written, I marvel at the sheer weight of the words stored here. The immensity of volume. The written displays state that as the British Library is a legal deposit collections they have a legal duty to collect and preserve every copy of every book, newspaper, magazine and map published in the UK, as well as printed music. Since 2013 that includes the UK web archive. The sheer cacophony of words - the poetry and politics, descriptions and drafts, evidence and headlines. If ‘Night at the Museum’ was made in the British Library there would be all out war. A place where the om mani padme hummmm becomes a futurist zang tum tummm collision of ancient and modern prophets and profiteers. A place where peace has to be fought for. I sit in front of the towering glass walls of the temperature controlled ‘Kings Library’ bequeathed to the nation by King George III. Books as beautiful objects to care for and conserve for generations. But the words - the words contained in this ocean liner are wild – an ark with wondrous, dangerous cargo. Words inciting hate and revolution, love and war. Words that sing across centuries of the best and worse of what it is to be human in our journey around the sun.

The collections grow by 8km and 500 terabytes a year. How can they keep growing in the finite space of underground London and a 43 acre at Boston Spa? This is the same kind of incomprehension and wonder I feel thinking about how the world isn’t one big cemetery. All we are is dust in the wind. But where are the terabytes? What is the physical footprint of our digital lives? How much energy does this take? The constant hummmm of servers serving this operation. A hummmm is overwhelming the calm of study, in the life drawn to these words. Arundhati Roy states “Another world is not only possible, she is on her way. On a quiet day I can hear her breathing.” I can hear her roar.

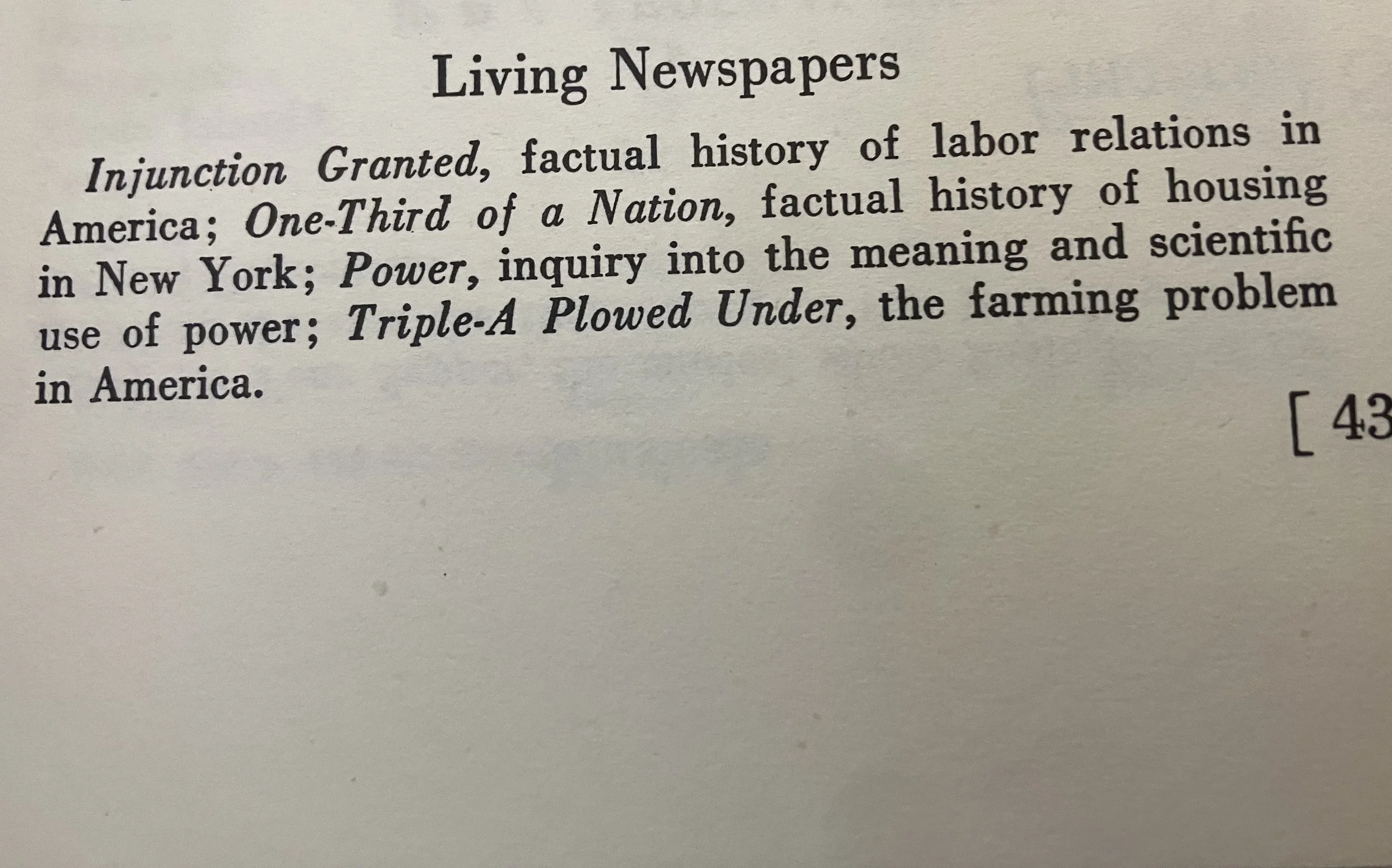

So amid these musings I move to get on with what I came here for – deeper research into the Living Newspaper Unit of the Federal Theatre Project. The context it emerged from – The Great Depression and Roosevelt’s New Deal US. The way these plays were made - scripted from headlines of the day, employing unemployed journalists. Their staging inspired by Soviet Constructivist Theatre, their innovative use of analogue technology and multi media. The way they were censored and banned. The House of UnAmercian Activities.

I double check I am meeting the reading room requirements. My own requirements. Don’t spend too long writing this as a first rule. 1 hour max. Compartmentalise by day. But leave room for diversions. Of which I instantly find one – checking the dates of the Kings Library I see that Jonathan Swift had similar ideas writing ‘The Battle of the Books’ in 1704 – a satire depicting a literal battle of books in the library. Results left inconclusive by describing the manuscript as damaged. Illegible in parts. Like history. Like life.