Wed 8 October 2025

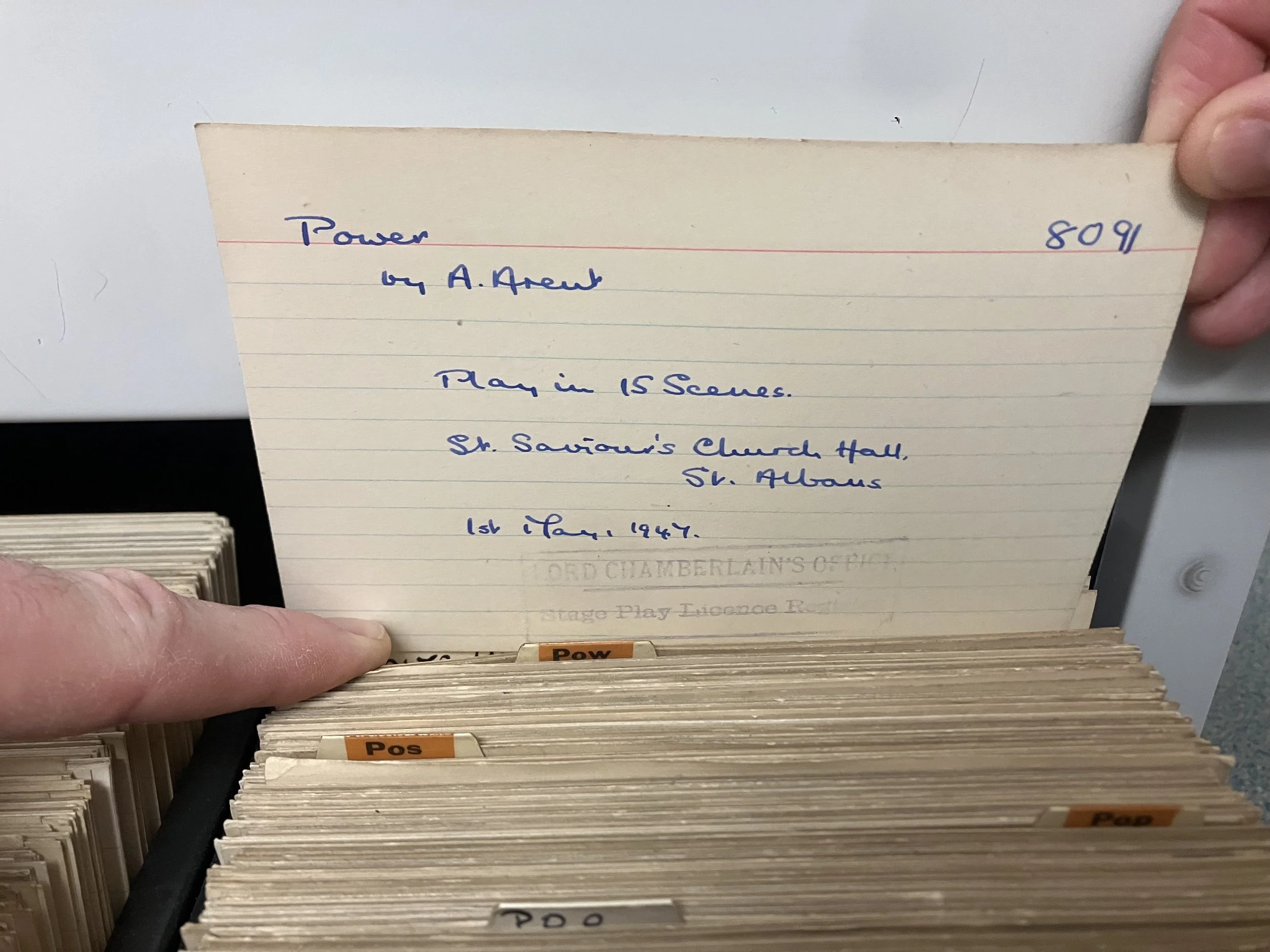

FLICKERING

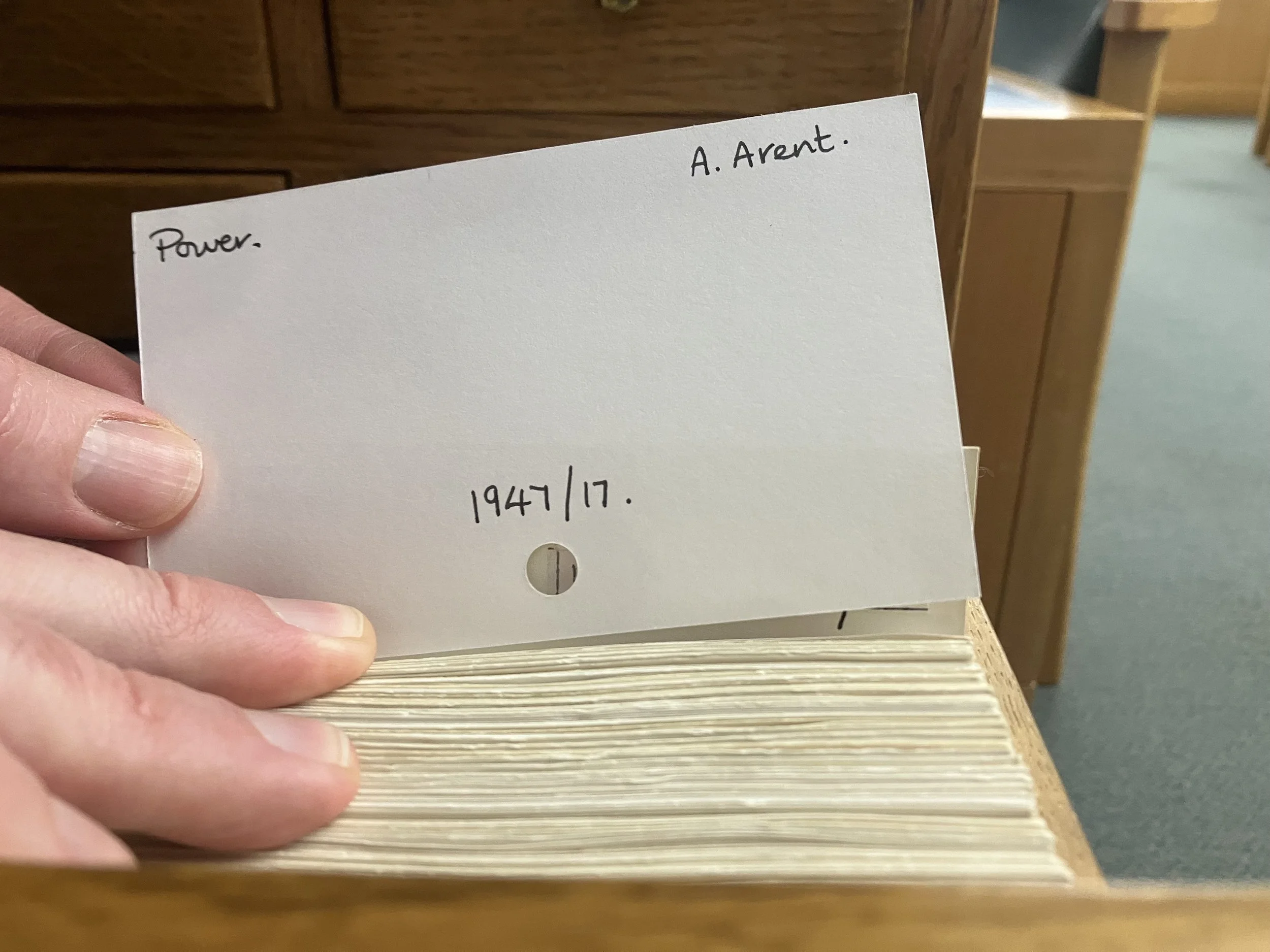

For a silent space it sure is noisy. The click clack of clumsy typing invades. It’s not even coming from the PC terminals but an old laptop in the wrong hands. Various unidentified hums and hisses echo. I arrive exhausted but this place gives focus. If it wasn’t for the sausage fingers next to me. After fruitless trips to Humanities 2 and Rare Manuscripts in search of books that are now en route back to Yorkshire with short staffing meaning there could be a delay of 3 weeks until I can read ‘Art for the Millions.’ Rare manuscripts was plan B – read the POWER manuscript from the Lord Chamberlain’s archives. A promise of keeping it for me for this day unrealised means it must be reordered. Only it can’t be found because the whole system is offline. Wifi unavailable. The systems we construct unstable and fragile no matter what aura of permanence.

I look at the short pencils and assorted pencil sharpeners available at the desk and see a fallen soldier on the computer monitor base. A little plastic soldier randomly placed. WAR what is it good for, absolutely nothing.

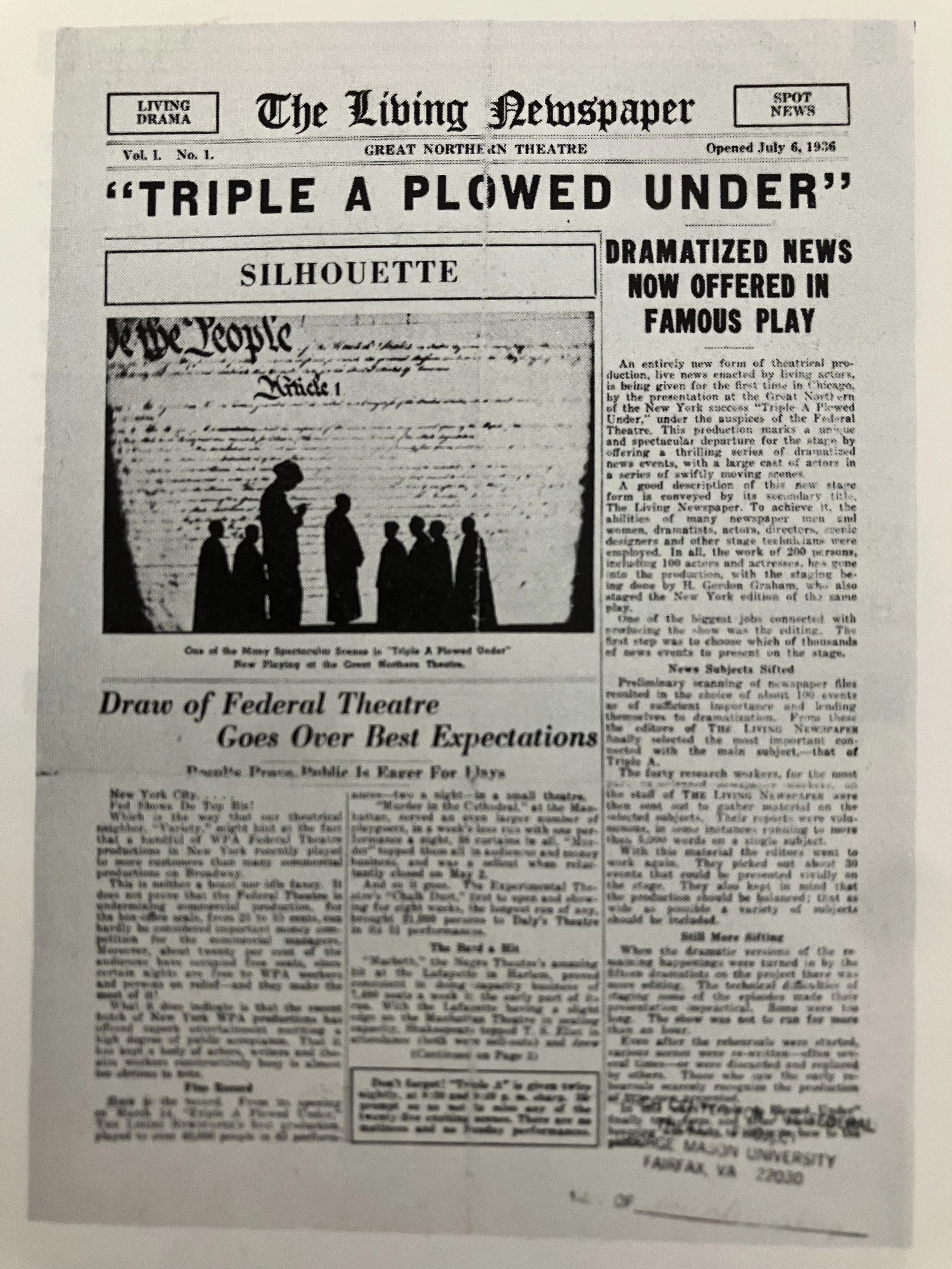

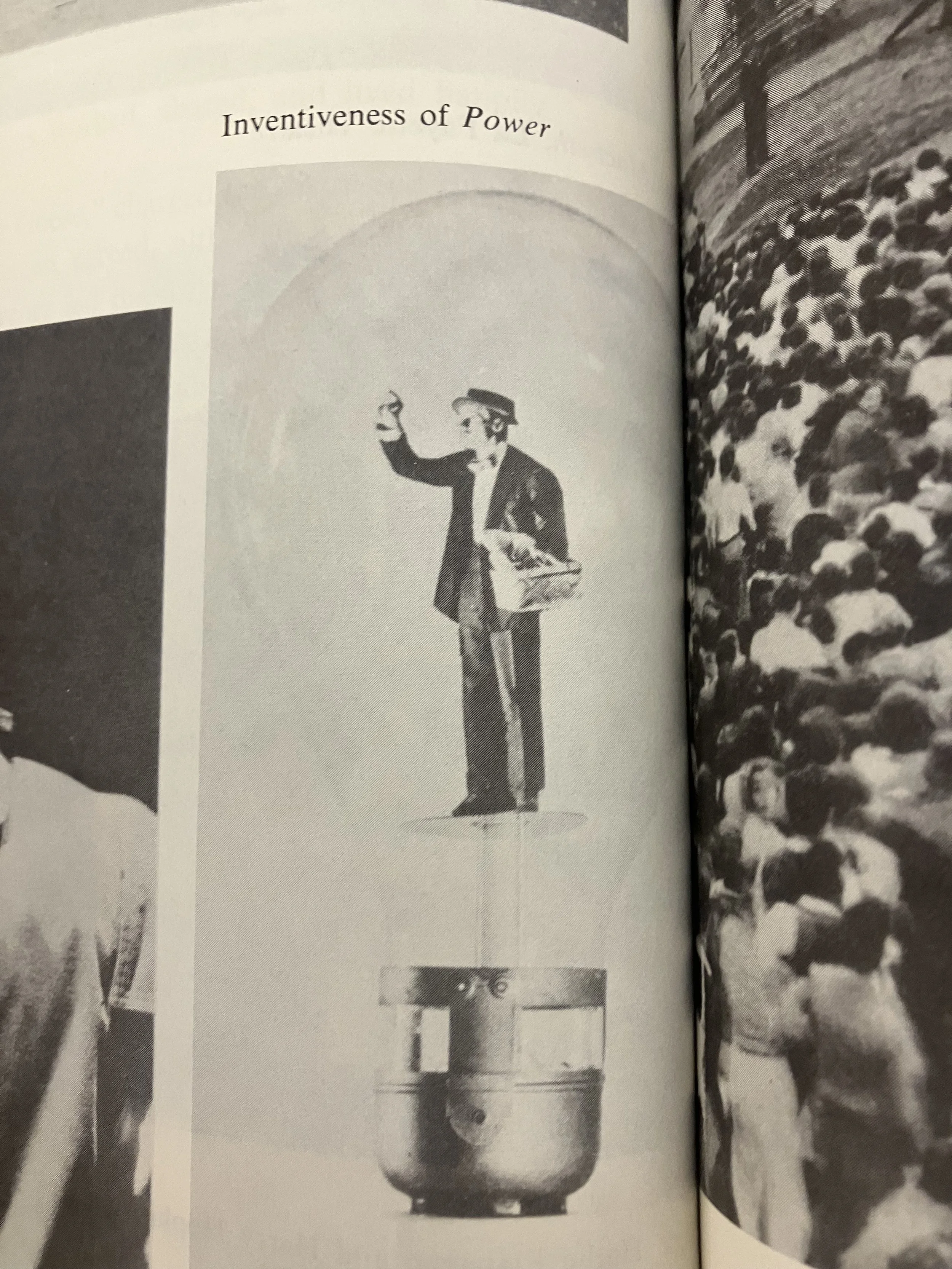

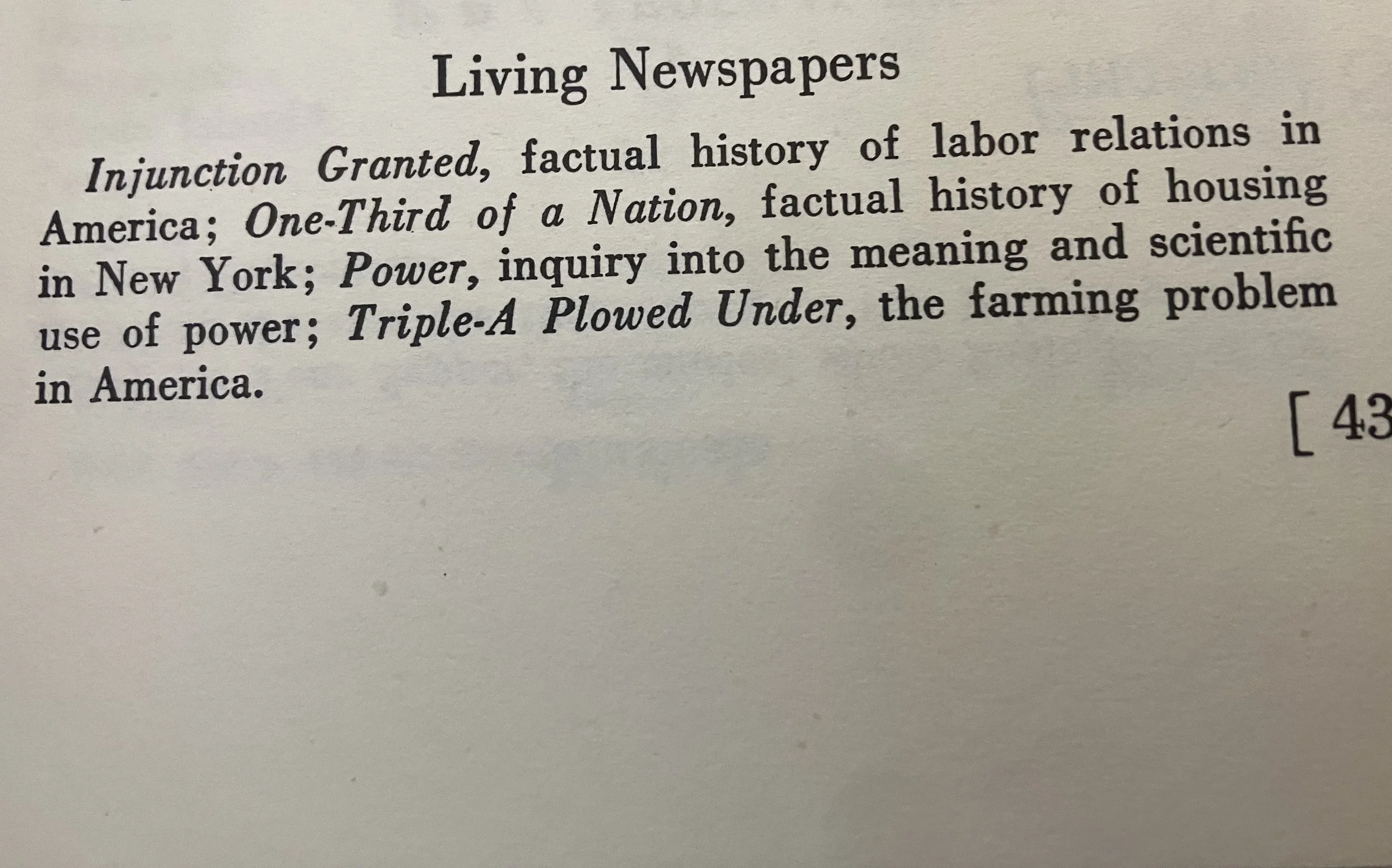

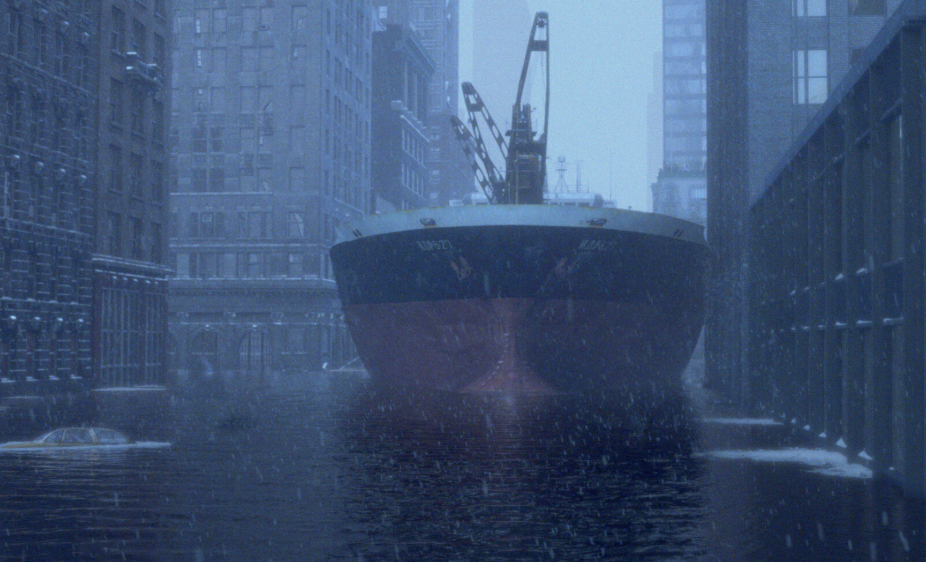

I ‘ve got into a rhythm. But I am not here as a reader. Research is not enough on its own. I need to make something. Make something happen. I am a ‘fellow’. Something about fellowship is life. William Morris. The kind of fellowship that implies participation and communion - though looking up its etymology there is something more transactional and property based at its root. Fellowship as sharing is obvious in the work that is currently being released across the country in the form of the POWER STATION. Someone asks “you’ve tackled finance, energy – what next?” media? And now I work out what this ‘Living Newspaper Unit’ is.

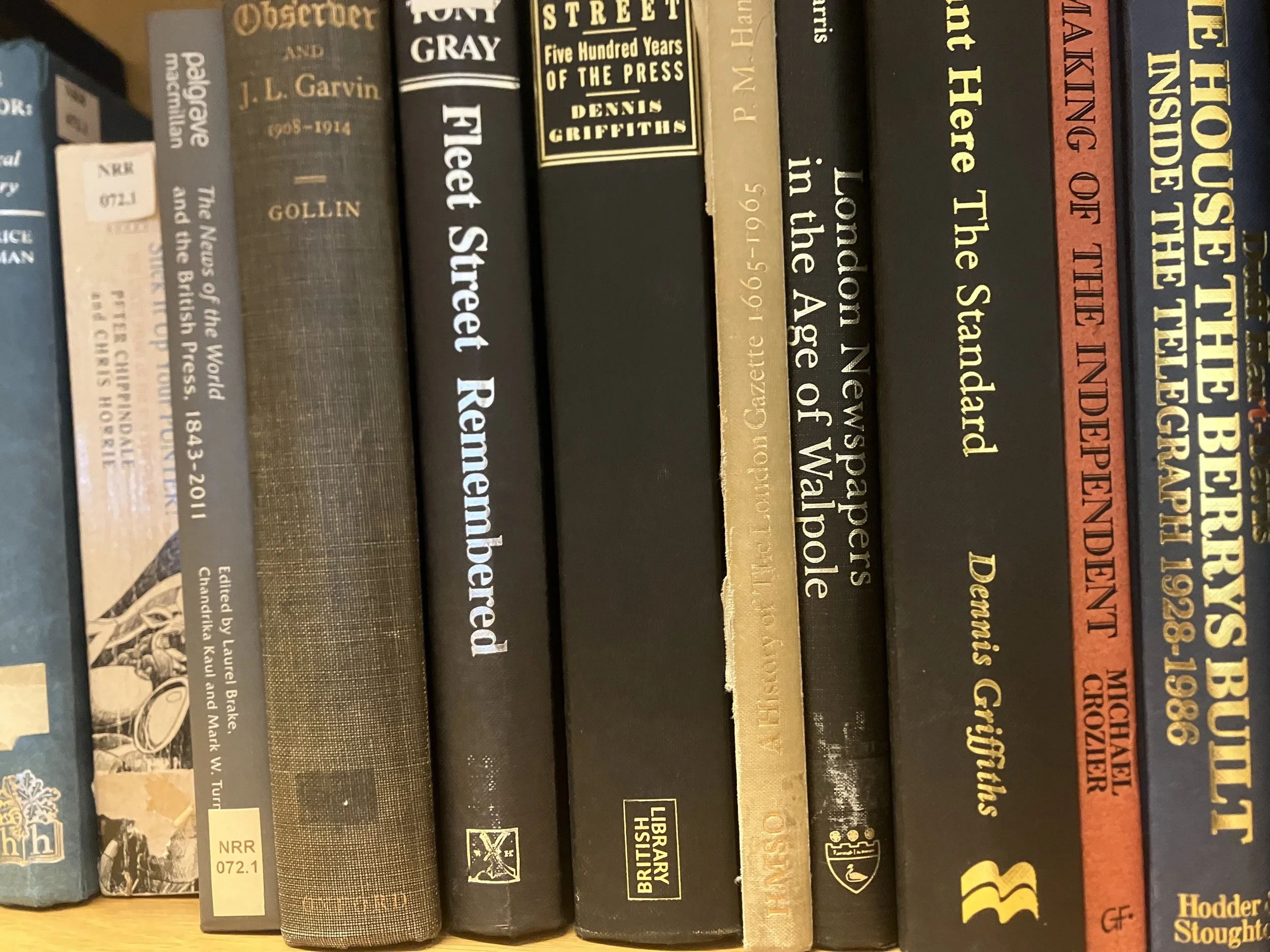

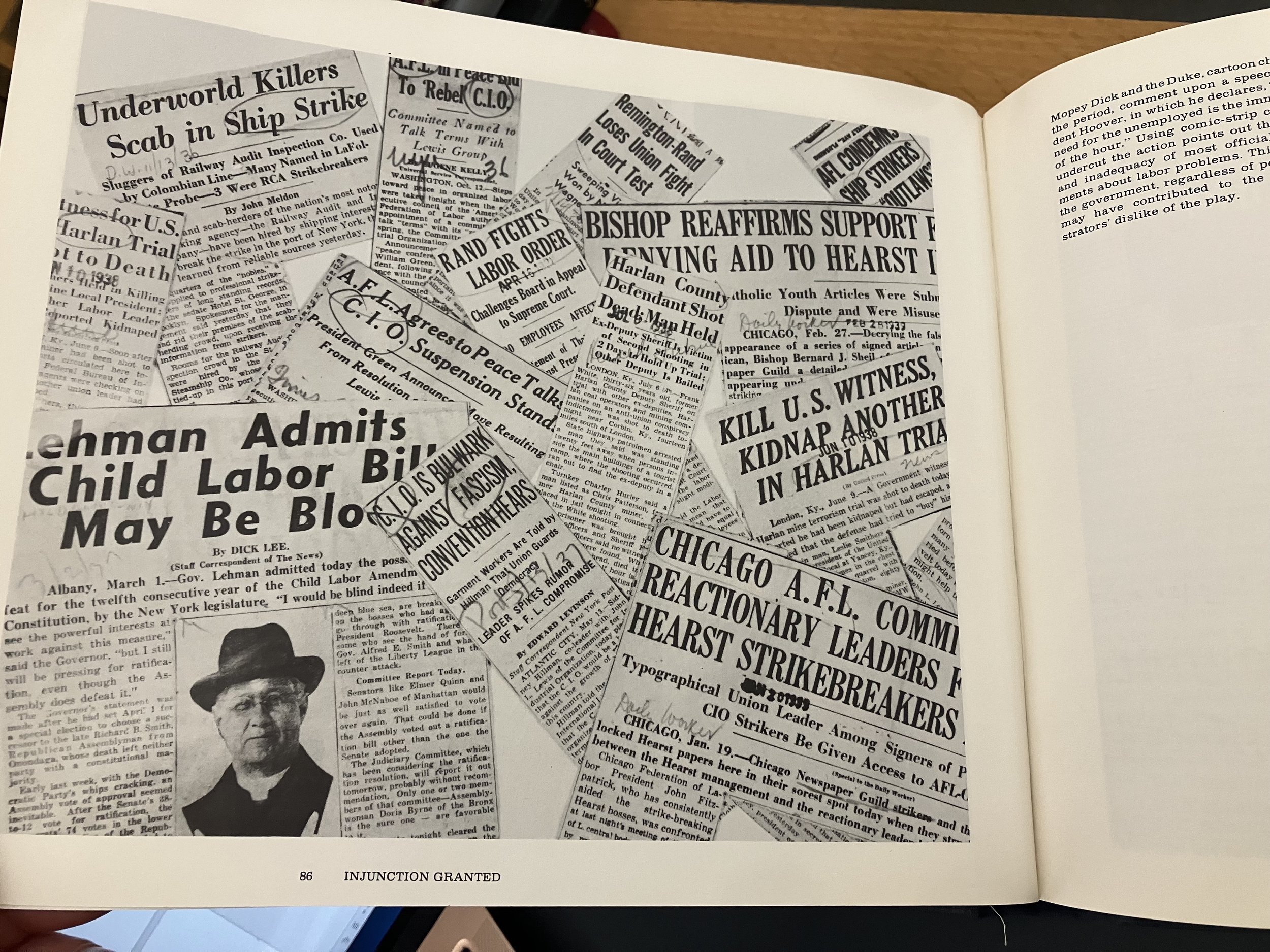

Today is disjointed. Books and manuscripts lost in the system between times. Between sign off and return. I feel similar. Full of questions. The pressures of a film release. Of press and being public and exposed. Seeing behind the scenes of news cycle and media industry. Observing the obsessive quest for the new in news. The hunt for the angle. Hacks and hacking.

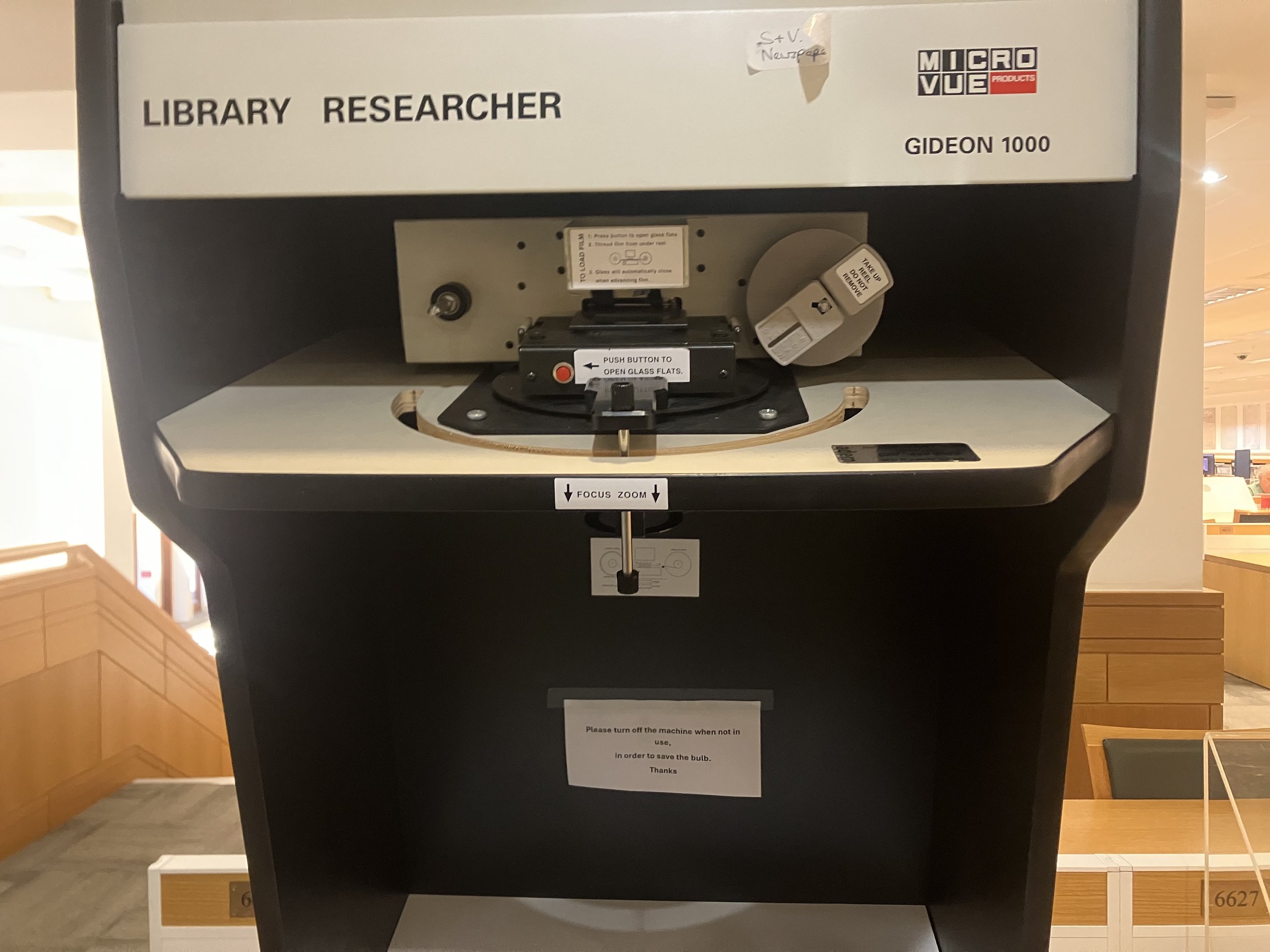

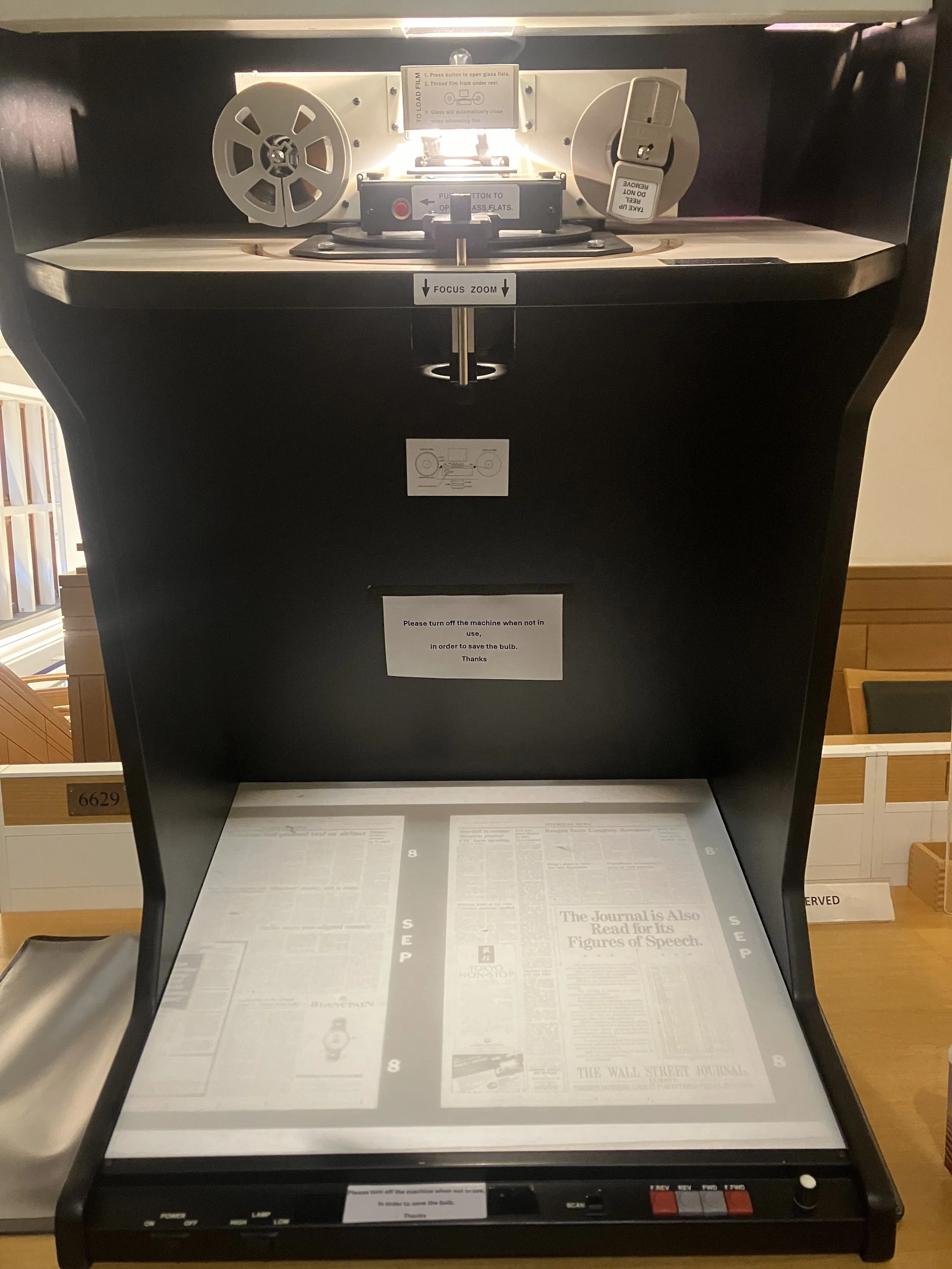

And then - things shift. I return to the newsroom and ask about the big machine sitting dormant – the ‘Library Researcher. MicroVue. Gideon 1000.’ Apparently the cyber attack meant these machines of another era emerged from the basement as the only way to access reels and reels of newspapers. Is there anything particular you want to view? Right now I just want to view the process – so I randomly pick 1986 Financial Times. A year of pink papers now stored in monochrome black and white on a single spool. I’m shown how to thread them through the machine. There are rows of digital viewing machines for these films but I’m drawn to the light - the projection bulb and ‘stage’ that the news is beamed onto from above. FF. REW. Manipulating this archived time capsule. It reminds me of my pop-up book. All the worlds a stage. Oh oh that Shakespearian rag.

What print? What participation? So perhaps the most useful thing I can do today is tasks:

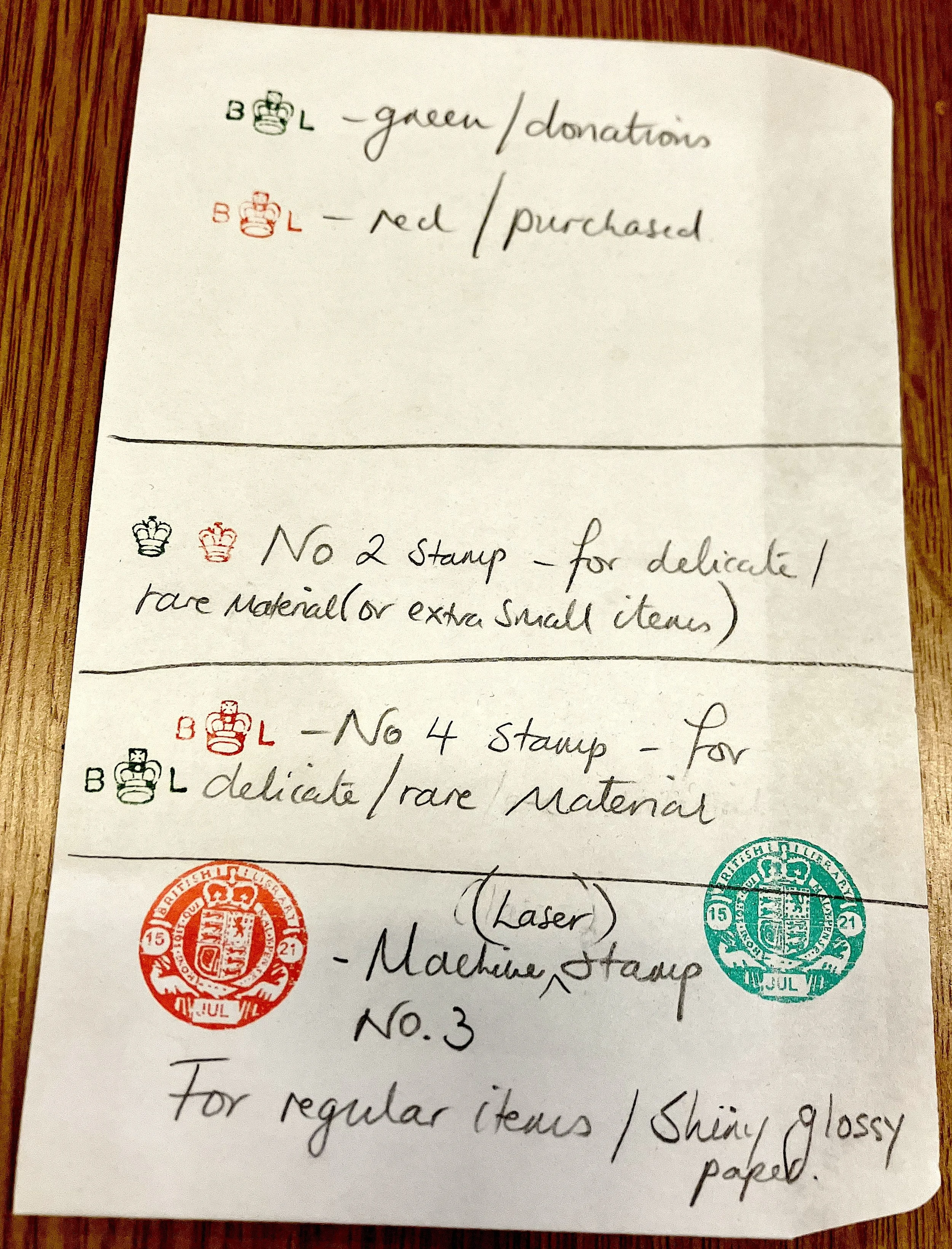

Go back to the manuscripts collection and get hold of the script for POWER. Follow up on the books that have been returned. Organise a trip to Yorkshire to the Boston Spa facility. Collect newspapers daily now – look at paper type and fonts. Look at other artists working with cut up and newspaper and how this can’t be that. Think about elements of participatory making – reflect on POWER STATION – different phases of research, preproduction, production. When it is lone? When it is collaborative? Set up microfiche machine. Understand how it works and the potential of sheet imagery. Check out the newsroom machine - what works best as a form of stage? Look online at the Library of Congress documentary images of the plays – get in touch.

But this makes it all look too neat. Organised in words. On a page. Really synapses flare with doubts, deletions, asides. It is the beginning of October. There is time to dig deep. Time to create a ‘call’ or ‘invitation’ ready for a new year. Time to cut and paste and spool through flickering images and ideas.